|

William Hogarth Biography

Active 1721-1764 in England, Britain,

Europe

Hogarth was the first, great, visual artist born and

bred in England. His achievement is remarkable

for its range, quality and originality. He created major works in book illustration, individual portraiture, small group portraiture,

or “conversation pieces”, and grand history-painting. Most memorably of all, however, he created a new genre of

narrative comic history-paintings, or “modern moral subjects”, as he described them in his Autobiographical Notes,

which established satire and comedy in art as high and respectable categories worthy of serious attention. He then used his

skills, acquired as an apprentice silver-engraver, to translate his paintings into print form and make his work available

to a wide, popular audience. As a consequence Hogarth’s fame as a print-maker exceeded his fame as a painter and his

work took on a distinctively literary dimension. The viewer has to learn how to read a Hogarth print not just how to look

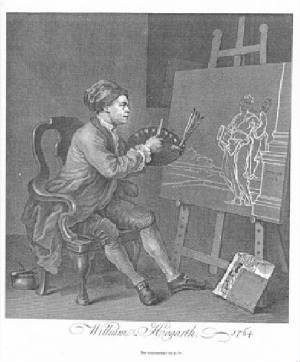

at it. Every detail has a narrative, or emblematic, significance. Hogarth acknowledges this literary dimension in his famous

self-portrait of 1745, a painting within a painting, in which his oval-framed self-portrait rests on three bound volumes,

marked Shakespeare, Milton and Swift, indicating his desire to be thought of as drawing on, and sharing in, the English literary

traditions of the theatre, epic and satire.

William Hogarth was born in Bartholomew

Court, next to Smithfield, close to the heart of the City of London, on 10 November 1697, the son of Richard Hogarth, a struggling

schoolteacher and writer of Latin textbooks. The family was not destitute, but it was always poor, and in 1707, when William

was not yet ten, his father was confined to the Fleet Prison for debt after his Latin-speaking coffeehouse failed. He remained

there, or in its close environs, for five years till freed by an act of amnesty in 1712, but his spirit had been crushed and

he died six years later in 1718. His family’s experience, and particularly that of his father, deeply influenced the

growing boy and much of his work is infused with images of imprisonment and sympathetic representations of the poor. He seems

to have determined from an early age to ensure that he achieved sufficient financial independence to avoid such a fate.

In 1714, when he was sixteen, he was apprenticed to Ellis Gamble,

a silversmith, with whom he stayed for six years, learning the skills of an engraver, which served him so well in later life.

In 1720, aged twenty-three, he set up his own business as an engraver in his mother’s house in Long Lane, working on

tankards, snuff-boxes and silver-plate, as well as producing shop-cards, book-plates and letterheads. As early accounts show,

William possessed a spirited and tenacious nature and it is not without significance that his first surviving print, engraved

in 1721, but not published till 1724, should have been a satiric response to the South Sea Bubble of 1720. The South Sea Scheme

shows an allegorically crowded scene of frantic, greedy activity around a wheel of fortune, used as a merry-go-round, turned

by directors of the South Sea

company and ridden by a range of subscribers. Other satiric prints, in similar vein, followed. The Taste of the Town, or Masquerades

and Operas, attacked the present state of the theatre, “debauch’d by fool’ries”, and the vogue for

Palladian architecture. Twelve large prints, published in 1726, illustrating Samuel Butler’s poem Hudibras, mocking

extreme Puritanism, showed his penchant for burlesque and The Punishment Inflicted on Lemuel Gulliver, published in December

of the same year, just after the first appearance of Swift’s great satire, elaborated on Swift’s fiction by showing

his hero being given an enema as a punishment for extinguishing the fire at the Royal Palace. Hogarth’s target in all

these prints is the credulity of the populace.

His enthusiasm for engraving, however, gradually waned as he came

to feel that it represented too restricted, even too mechanical, a skill. He increasingly turned to painting, in which medium

he felt he could express his creativity more freely, quite apart from earning better money. He had met Sir James Thornhill,

the leading English history-painter of his day, sometime in the early 1720s and begun attending his academy in Covent Garden in 1724. Hogarth seems to have decided to turn definitively to oil painting as his primary

means of expression during 1727 and the following year began painting The Beggar’s Opera, the popular, theatrical hit

of the time. Its prison scenes and low life zest seem to have struck a particular echo with him. Over the next eighteen months

he painted at least five versions of it for different patrons.

Perhaps his growing interest in painting was heightened by his feelings

towards Thornhill’s daughter, Jane, and on 23 March 1729 he secretly married her, in Paddington, without her father’s

consent. They settled down in Covent Garden, not far from her parents, and Hogarth set about

developing his reputation as a painter of portraits and conversation pieces. In the late 1720s he painted a considerable number

of these, none more admired than his fine portrait of the prosperous and powerful Wollaston Family, executed in 1730. Painting

portraits and conversation pieces was far more lucrative than engraving prints for booksellers and Hogarth’s portraits

soon became sufficiently in demand in the polite world to allow for reconciliation with his father-in-law.

It was in 1730 that, according to the eighteenth-century diarist of

artists’ lives, George Vertue, Hogarth fell, almost by accident, on the idea of painting A Harlot’s Progress.

He had painted a whore and her servant in her garret in Drury Lane

and developed the idea of tracing both her previous and subsequent histories. The six paintings of A Harlot’s Progress,

including the likenesses of well-known contemporary persons, were the result. These pictures became very popular and, people

pouring into his studio to see them, he hit upon the further idea of making engraved copies of the paintings and selling the

prints, by subscription, at a guinea a set. The prints were published on 10 April 1732. All 1,240 sets were sold and, at the

age of 34, Hogarth suddenly found that his fame and fortune were established.

Hogarth could now afford to move to Leicester Square, as it is known today, and set up his own studio there under the name

of “The Golden Head”. The success of A Harlot’s Progress invited an obvious sequel and Hogarth next set

about eight paintings depicting A Rake’s Progress. The weakness of Hogarth’s new-found source of wealth, however,

was that there was nothing to stop any engraver buying a set of the prints of A Harlot’s Progress, re-engraving them,

and selling the pirated copies at a cheaper price. This is exactly what happened, but Hogarth was never a person to take a

challenge lying down. In February 1735 he arranged for An Engravers’ Copyright Bill to be drafted and introduced to

the House of Commons. On 15 May 1735 the Act, which became known as Hogarth’s Bill, received royal assent and passed

into law. A month later, on 26 June, he released the engravings of A Rake’s Progress, which he had held back until the

Act had been passed. This time he was able to charge subscribers two guineas a set. Hogarth became the acknowledged leader

of the artists of the day, showing them how to organise themselves so as to establish their independence from patrons and

improve their status in society.

Hogarth’s energy around these years was boundless. He was the

moving spirit in founding St Martin’s Lane Academy,

the cradle of a new ‘English School’

of painting. He embarked on two grand history-paintings, The Pool of Bethesda and The Good Samaritan, in which the figures

were seven foot high, for the great staircase of St Bartholomew’s Hospital, where he was a Governor. He painted a number

of social, satiric subjects, The Distressed Poet, Strolling Actresses Dressing in a Barn and Four Times of Day, and followed

these up with engravings of each. He painted many single portraits, including his superb portrait of Captain Thomas Coram,

founder of The Foundling Hospital, of which Hogarth became a Governor, donating his portrait of Coram.

In 1742 Hogarth’s friend, the novelist Henry Fielding, praised

him, in his Preface to Joseph Andrews, as “the ingenious Hogarth”, who made his figures not just seem to breathe,

but “appear to think”. Fielding described Hogarth’s work as “comic history-paintings” and placed

his achievement in art alongside his own comic epic in prose. This elevated Hogarth’s painting to a higher and more

respected plane, and he responded by beginning work on a sequence focusing on high life, Marriage à-la-Mode. This series of

six paintings satirises the emptiness resulting from arranged marriages, poking fun at the respective profligacy and meanness

of both the aristocratic and merchant classes. This time Hogarth visited Paris to hire engravers who could give the prints

a somewhat more elaborate, rococo, French flourish, in keeping with his subject. In May 1745 he published the prints of Marriage

à-la-Mode , as usual by subscription, engraved by three French engravers, G. Scotin, B. Baron and Simon Ravenet.

In the same year he demonstrated his commercial independence again

by arranging an auction of his paintings at his own premises, thus cutting out the established art auction houses. The sale

realised nearly £500 for nineteen paintings. In October 1745 he completed his wonderfully theatrical portrait of his close

friend David Garrick as Richard III, as well as painting his own self-portrait entitled, The Artist with his Pug. The following

year saw another grand history-painting, Moses brought to Pharaoh’s Daughter, completed for The Foundling Hospital.

Then in August he demonstrated his eye for a business opportunity yet again by travelling to St Albans to see, and draw from

life, the Highlander, Simon Lord Lovat, attended as a captive on his way to London

to face trial for his part in the Jacobite uprising of the previous summer. Hogarth’s ensuing print sold 6,000 copies

at a shilling each, earning him £300.

Hogarth’s business opportunism sat alongside a strong, philanthropic streak. In 1747 he set out to demonstrate

his concern for the education of the young, especially of young foundlings, by producing a series of twelve prints of an explicitly

moral tone, illustrating the respective benefits and dangers of serving good and bad apprenticeships. Industry and Idleness,

tracing the contrasting careers of two apprentice weavers, Frank Goodchild and Tom Idle, is a “modern moral subject”

of a distinctively different order to the earlier sequences. This time Hogarth worked directly to the etchings (there were

no initial paintings for the prints to become mirror images of) and did so in a much more clear-cut and direct style aimed

directly at young apprentices. Carefully chosen scriptural texts, at the foot of each print, rammed home the point of the

illustrations, should anyone be in any doubt about them, and the prints were sold at the cheaper price of a shilling each.

Although this was still far more than any apprentice could possibly afford, Hogarth clearly hoped that their masters would

purchase and display them as a form of instruction and encouragement.

In the summer of 1748 Hogarth set out for France in the company of

some friends, but his inveterate distrust of the French, partly related to their Catholic support for the Jacobites, caught

up with him in Calais when he was arrested while sketching

and expelled for ‘spying’. He rapidly got his own back by painting

and then publishing a print called The Gate of Calais showing a huge sirloin of beef being carried to an English eating-house,

and scrawny French servants in rags and clogs as its central contrast. The print fed anti-French fervour and Hogarth was acclaimed

a true, beef-eating, English hero. By September of 1749 he was well enough established financially to be able to buy a country

house in Chiswick, a quiet village a few miles upstream from London,

which he and Jane could use as a weekend retreat, especially during the hot, sticky summers.

Hogarth did not belong to any political party, but his work nearly

always has political significance. This is particularly true of the work he completed as he became more assured and established.

The March to Finchley, which he painted in 1750, five years after the Jacobite uprising had been put down, is a complex, satiric

attack on the sordid realities of war. A similar, fierce conviction informs the two prints, Beer St and Gin Lane,

published in February 1751 in support of the campaign to pass the Gin Act, which proposed a doubling of the tax on gin and

a severe limitation on where it could be sold. At the same time he published The Four Stages of Cruelty, a narrative account of the life of Tom Nero, a cruel

boy who ends up receiving his own ‘just’ reward on the dissecting table of the Royal College of Physicians. All

these prints were sold at a shilling each and were attempts to do something constructive about the appalling poverty and cruelty

so widespread on the streets of London.

Without ever being an art theorist, Hogarth had always thought deeply

and argued vociferously about the nature of beauty and art. Over the years he had vigorously challenged the connoisseurs,

who valued ‘Old Masters’ to the exclusion of all else, and the prevailing cult of Palladianism, particularly as

associated with Lord Burlington and William Kent. Hogarth did not find it easy to express his ideas in writing, but he struggled

to do so and in 1753 eventually published The Analysis of Beauty, “a short tract wherein objects are considered in a

new light, both as to colour and form”. His central argument is that the essence of beauty lies in “composed variety”

rather than regularity and straight lines. It lies in what he calls “the serpentine line of grace”, a waving line

informing all objects, both externally and internally, that “leads the eye a wanton kind of chase”. For Hogarth

meandering contours are inherently more beautiful than rigid outlines.

The winter of 1753 saw Hogarth starting work on what was to be his

last great comic history sequence, Four Prints of an Election, satirising the deep-rooted corruption of the electoral system.

This project took some time to complete and the final sequence was not published till March 1758, and then only with the help

of French engravers. Hogarth was, however, engaged in a number of other projects at the same time, including work on a grand

triptych, showing the Resurrection, for the altar of St Mary’s Redcliffe, Bristol,

and a number of portraits, including one of David Garrick and his Wife. Hogarth was now widely accepted as the pre-eminent

painter in England and, despite his prickly

and stubborn independence of mind, was appointed, in September 1757, on the eve of his sixtieth birthday, Serjeant-Painter

to the King, giving him responsibility for the appointment of all royal commissions for painting.

Hogarth’s final years, and particularly the two last years of

his life, were embittered by disappointment, poor health and personal battles. His attempt to create a sublime, tragic painting,

Sigismunda, to match his greatly admired, comic painting, The Lady’s Last Stake, was not well received, and when he

announced in March 1761 that he was going to publish a print of it he had to abandon the project for lack of subscribers.

Then on 7 September 1762 he made his first and only entry into party politics when he published a print called The Times supporting

Lord Bute and ridiculing Pitt and Temple from whom he had

just taken over. The move was disastrous, flying in the face of the mood of the country and, more to the point, in the face

of his erstwhile friends, the M.P., John Wilkes, and satirical poet, Charles Churchill, who both supported Pitt. Wilkes replied

immediately by devoting the entire issue of The North Briton, No. 17, of which he had recently become editor, to attacking

Hogarth in savage and blunt terms. Hogarth was badly hurt and responded on 17 May 1763 with his print of John Wilkes Esq.

showing him as a demagogue manipulating liberty for his own ends. A month later Churchill published An Epistle to William

Hogarth, accusing Hogarth, in ringing couplets, of betraying his fellow artists and of being full of overweening pride and

vanity. He portrayed Hogarth as a dotard on the verge of death. Hogarth was deeply stung, and in July suffered a paralytic

seizure, but he had never been a man to give up a fight and, determined on revenge, reworked his self-portrait of 1745 to

show Churchill as a slavering bear

too drunk to do anything about Hogarth’s dog who pisses on his epistle. It was a strangely rash response and in replacing

his own portrait with that of Churchill’s, albeit as a bruising bully, Hogarth conceded a certain victory to Churchill

that can be seen, at one level, as implying a kind of death wish. Hogarth managed one last print, Tailpiece: or The Bathos,

published in April 1764. In this allusion to Durer’s Melancholia, intended to serve as an endpiece to a complete set

of his engravings, he extends his own imagined end to cover that of the whole world. Father Time lies expiring, propped up

against a crumbling tower, facing a collapsing tavern sign bearing the name “The World’s End”. All around

are symbols of dissolution and decay, and at his feet a broken palette. The painter’s time was done. He finally died

of a ruptured artery shortly before his sixty-seventh birthday on 25 October 1764. He was buried a week later in St Nicholas’s

churchyard, Chiswick.

Hogarth was a great comic artist with a wonderfully observant eye for the details of everyday life, who longed

to be equally well recognised as a great painter of high art. It was paradoxically his youthfully acquired, and personally

least valued, skills as an engraver that brought him his greatest fame both in his own and later times. In addition to his

artistic genius he possessed an instinctive business acumen. He was a self-publicist who consciously gave his work a greater

notoriety and topical relevance than any previous English artist. He was actively involved in the major social and cultural

issues of his day. He was a philanthropist who played a major part in the development of both St Bartholomew’s and The

Foundling hospitals, and was strenuously engaged in trying to achieve a higher status for painting in England. His Analysis of Beauty gave a new dimension to debates

concerning the understanding and significance of art and struck a blow towards establishing an English school of art. Hogarth

was a major figure in the artistic, political and cultural life of the first half of the eighteenth century and illustrated

it so graphically that one still frequently comes upon references to his period and place as the age of Hogarth, or as Hogarth’s

London. He embraced middle-class virtues, especially industry

and piety, but did so with irony, wit, independence and compassion. He was a great humanitarian who used his art as a medium

for exploring human suffering and exposing human affectation.

|